Writing reminds me of the work of a landscape architect creating the structure of a garden.

People know how to move through gardens. Provided paths, they walk on them. They circulate as the designer planned, contemplating their surroundings as they go. Perhaps the lazy and incurious won’t bother to take in a proffered view, but that wouldn’t be the garden’s fault.

Maybe the hardest academic skill I teach is writing a trail of reasoning for readers to follow, a pathway of original analysis moving around the works we’ve read. Here is the difficulty: Because we read sentences in order, whenever writers produce a string of them, they have the look of a path even when they don’t produce the feel of one. But a flow of information, statistics, and quotations is like mentally marching in place until the writer’s purpose with all that starts to lead somewhere interesting.

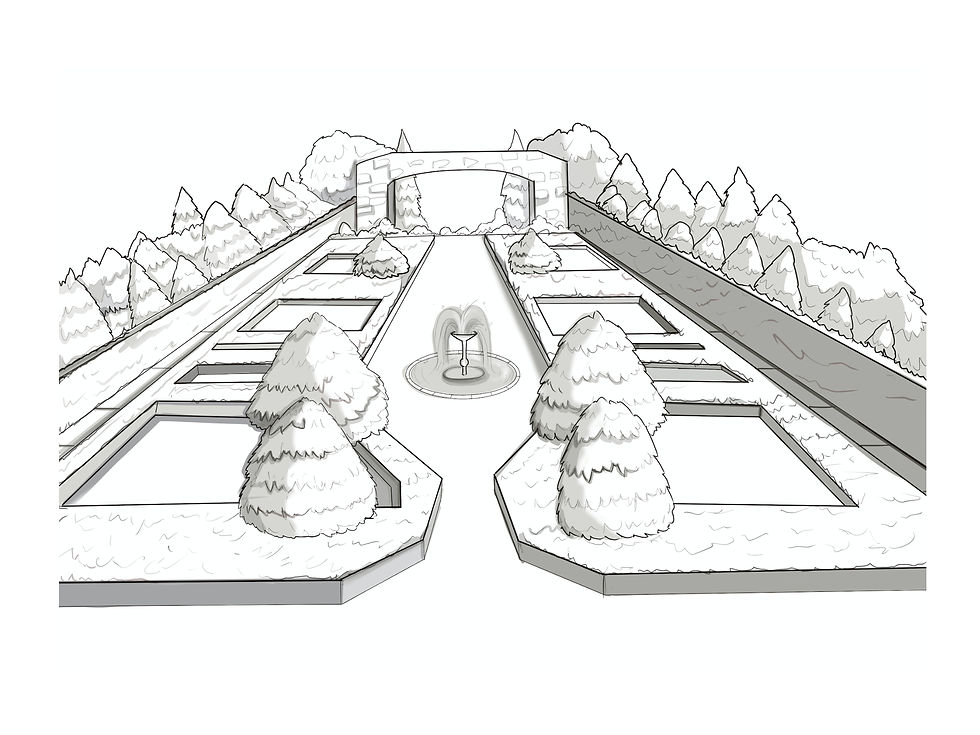

Imagine the texts I assign as so many trees and shrubs ready for a gardener’s use. I deliver a flowering dogwood tree, cypresses, and a blue spruce, and I ask my students not to be satisfied with writing [thinking] like this:

A garden has three parts: a dogwood tree, a cypress, and a blue spruce.

The dogwood flowers in springtime.

The cypresses can grow tall.

The blue spruce has a piney smell.

[This only shows organization.]

I ask: How about taking a risk instead? Why not get in there and say something?

Cypresses belong in a row because they are good at making a barricade and can create the feeling of a room. Stand before a row of them and sense the living wall, so much friendlier than stone. Plant one in the middle of a lawn and feel the mistake, so skinny and alone. They look like columns, and does a single column, especially a wispy one, belong by itself in the middle of nowhere? The feathered arms of cypresses look like they want to grow and touch. [I imagine a reader objecting here: Not true! What about that famous Lone Cypress in California? But a thought-provoking claim will produce critique and questions. Good.]

The blue spruce is another matter. [See the shift in reasoning? This paragraph builds on the previous one to establish a contrast.] First, it’s a different, cooler green, perfect for making a statement. As evergreens go, it’s like a friend who isn’t afraid to wear a larger pattern or neon yellow shirt. In contrast to the cypress, the blue spruce looks happy as an individual. It could be its wide base just makes it look more confident on its own, like it wants to claim a big circle of ground for its little pointy top, thank you very much.

A flowering dogwood can also make a statement, but it’s got a different strategy. [Yes, more contrast. Read on to learn why.] While the spruce will always be green, the dogwood’s leaves turn color in autumn and drop off. From its compact base, it spreads out multiple branches—gray, empty, patient all winter. In spring, for brief weeks, its arms radiate flowers and suddenly people really see the dogwood, but it subsides into muted, mellow leaves. In fall, it forms attractive red seedpods, but birds tend to notice these more than humans do. The spruce is always grand, but the dogwood lives like most of the people I know, going about its business in a quiet way most of the time, but much better than ordinary. [I just keep linking human characteristics and these plants. Turns out, that’s where my thoughts are tending.]

To understand the personalities of trees and shrubs, notice their shapes and behaviors. [This claim makes me panic a little. I’m no arborist! Can I say this? I like my claims but wonder how fair they are to the trees. What could this mean? Ah. Now I know the next step to take on my path and the view I’m discovering.] Just like studying humans, it’s hard to grasp where perception ends, and the trees begin.

Comments